The era of manufactured organs begins

And, with it, we step closer to immortality.

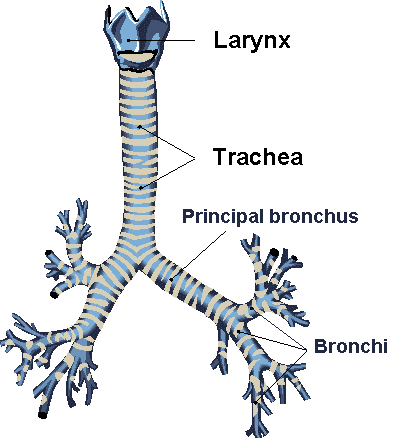

Claudia Castillo, a Colombian woman, became the first recipient of a tracheal transplant, where the trachea was built out of her own stem cells.

Sounds unbelievable, but what the doctors did was not that amazing once explained. They took a trachea from a donor, stripped it down with detergents until only the connective tissue proteins remained (in a sort of trachea "skeleton"), then let stem cells -- harvested from Claudia's bone marrow -- grow on it. This technique eliminates any possibility of transplant rejection by Claudia's body:

Researchers at the University of Padua, Italy, led by Maria Teresa Conconi, then used detergent and enzymes to purge the donated windpipe of all the donor's cells. After six weeks, all that was left was a solid scaffold of connective tissue.

Meanwhile, Birchall and his colleagues in Bristol took the stem cells from the patient's bone marrow and coaxed them in the lab into developing into the cartilage cells that normally coat windpipes.

Finally, the patient's cells were coated onto the donated tracheal scaffold over four days in a special bioreactor built at the Polytechnic of Milan in Italy.

Claudia was in need of an autotransplant because, when she suffered from tuberculosis, TB damaged her windpipe so much that her windpipe collapsed, leaving her without the ability to breathe normally.

Other people are already working in replacements for more complex organs, like kidneys:

But one of the side projects was the construction of an artificial kidney. The prototype was a 20cm diameter flattened oval glass container with a massive matrix of tubes inside for blood-flow, and then this container was filled with kidney cells grown in fermentors, with the eventual goal of using this as a very limited artificial kidney.

The project was in it's infancy when I saw it, but I am optimistic it's the basis for the future. Biocompatible material used to make a matrix, mature cells grown from adult stem cells and carefully coated to the support, and finally implantation.

Eventually, once the manufacturing techniques are sufficiently advanced, it will no longer be necessary for people to die while waiting for donors. Transplant rejection will also be a thing of the past, and patients will no longer have to take immunosuppressors to stave off organ rejection. More importantly, time won't be a factor in the search for cures to serious diseases like non-metastatic cancer, infarctions and renal insufficiency.

It's pretty clear to me that stem cell research and medicine have lots of surprises for us in the future. Let's hope they keep coming.